Christoph Elhardt for ETH Zürich

Mariam Issoufou is one of Africa’s most sought-after architects. She has held the position of Professor of Architecture Heritage and Sustainability at ETH Zurich since 2022.

Clay is one of the oldest building materials in the world. But in many places, the sticky, greasy mixture of clay and sand was replaced by concrete in the course of industrialisation. Something was lost as a result, says Mariam Issoufou, because clay is far more than just a building material: it is a bearer of culture and centuries-old wisdom.

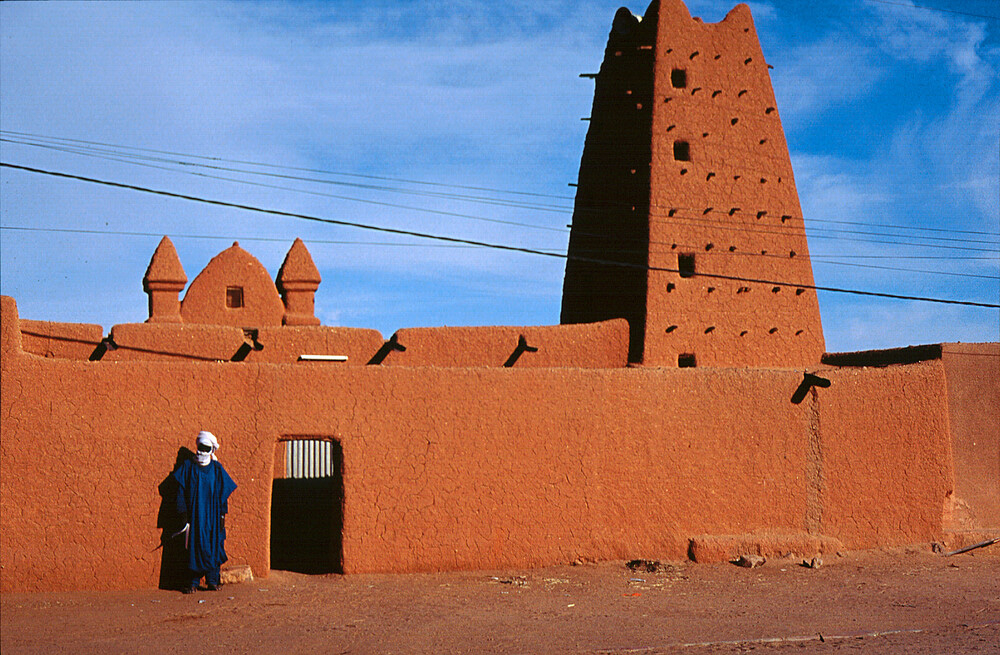

Anyone in Switzerland looking to understand what clay means to one of Africa’s most sought-after architects should head some 3,400 kilometres south to Niger, Issoufou’s home country. There, a minaret soars 27 metres up into the deep blue sky above Agadez, a small town in the centre of the West African country. The orange-coloured tower belongs to a large mosque and forms part of the historic old town, which was built in the 15th and 16th centuries. Like most of the buildings in the old town, the mosque is made of clay. This construction method is typical in desert regions; it’s not far from Agadez to the Sahara. From April to September, the temperature here is around 40 degrees.

Issoufou was six years old when she moved from the capital of Niger to the environs of Agadez. She lived there with her family on the edge of the desert for five years. “The old town of Agadez, with its flat-topped mud houses, gave me an early sense of the heritage of an African building culture that has been completely forgotten in the West,” Issoufou recalls today.

A feel for forgotten building traditions

How buildings protect people from heat is by no means an abstract problem for Issoufou. “Back then, it wasn’t unusual to walk home from school in temperatures of up to 45 degrees. I’ll never forget the feeling of stepping inside our cool mud house,” she says. Unlike people who grow up in the West, she wasn’t surrounded by houses made of concrete or wood during an important phase of her childhood. For centuries, clay was the standard building material used in Niger to insulate houses against the heat.

“It’s not as if things only got going in the first half of the 20th century with a few gods of modern architecture such as Le Corbusier or Frank Lloyd Wright.”

This feel for the architectural heritage of her homeland is a major part of Issoufou’s work to this day. Not least in her lectures, in which she teaches her students about forgotten building cultures. She wants to show that beyond the modernist mainstream in America and Europe, there are traditions from which Western students can learn a lot. To do so, however, they must first abandon modernism’s blinkered view of architecture. “It’s not as if things only got going in the first half of the 20th century with a few gods of modern architecture such as Le Corbusier or Frank Lloyd Wright,” she says.

For Issoufou, the dominance of modernism also explains the fact that for a long time, sustainability wasn’t an issue in architecture. “Only today do we realise that many forgotten building cultures were also sustainable because they had to withstand the forces of nature without reinforced concrete, central heating or air conditioning.” In the southern hemisphere in particular, there are traditions that can reveal ways of dealing with higher temperatures. “We have to rediscover these today,” she says.

Dovetailing with local building traditions

Issoufou was born in France but grew up in Niger. She came to architecture late in life. After completing her schooling, she was given the opportunity to study in the United States. At the time, computers seemed to be the surest way to gain a foothold in America. So she decided to study computer science, even though her heart was already set on architecture. She worked as a software engineer for seven years until she finally decided to return to university and study architecture in Washington after the age of 30.

Just ten years later, Issoufou is one of Africa’s most sought-after architects and has offices in Niger’s capital Niamey, Zurich and New York. In her projects, she always tries to pick up on local building traditions, as these preserve a great deal of knowledge about local conditions and problems. One example is her design for a centre for women and development in the Liberian capital Monrovia. The buildings with their high, steeply slanting single pitch roofs are inspired by traditional Palava Huts, whose roofs were designed to cope with the heavy rainfall in Liberia.

Fighting the heat with clay

From her very first projects as an architect, while part of the architecture collective united4design, Issoufou has consistently favoured the building material that she knows from her childhood in the desert. In 2016, the collective built a residential complex made of clay in Niamey. Issoufou , together with Yasaman Esmaili, also used clay bricks for a community centre with a library and mosque in the Nigerien desert village of Dandaji. She has shown that clay can rise to the challenge of modern architecture.

Issoufou argues that clay offers some very real advantages: “It comes straight out of the ground, it’s fully biodegradable and it’s much cheaper than concrete. The material also has very good cooling properties, which means it’s much better suited to the climatic conditions in Niger.” Issoufou’s choice of suitable building materials also conveys her criticism of modernism’s stranglehold on global architecture: “Concrete’s greatest triumph is that everyone believes it’s the only durable building material.” At ETH Zurich, she wants to pass on this critical eye for local conditions and forgotten building techniques to her students.